TRIGGER WARNING: This article contains sensitive content related to suicide, homophobic violence, militant attacks, conversion therapy, and discrimination against the LGBTQ+ community in Bangladesh, which may be distressing to some readers. Please read with caution.

In a room blanketed by silence, 12 people sat next to each other. For a long time, the only sound was that of a whirling fan. Then, one person spoke while others listened, helplessness evident in their eyes. In this safe space, carved out through years of struggle, their age, class, and education were not relevant. The only thing that mattered was their status as a sexual minority, a queer person.

These gatherings represented the idea of an egalitarian society I had always dreamt of. I was in the 36th session of our group meetings for mutual counselling, peer-to-peer support, and community-based mental health sessions in Dhaka, Bangladesh. I had initiated this group in 2019.

Amidst the sombre atmosphere of the room, my phone buzzed persistently with calls from an unknown number. When I finally answered, a woman’s voice on the other end introduced herself as Ritu*. She had attended an earlier session I had run on basic legal literacy, she said, and was reaching out for help.

“My girlfriend is in rehab at a conversion therapy centre, which her family is forcing on her. Please help us,” she pleaded. I stepped outside, a little dazed by the sudden influx of emotions. I tried to reassure her. “I am here to help you”, I said.

As I hung up, a sense of satisfaction settled in as I realised how the queer community in Bangladesh had developed a robust network over the years to support people like Ritu and her partner.

At that moment, my mind harked back to a few years ago, when we didn’t have such spaces of solidarity. I remembered a dark day when two people had become victims of brutality.

On April 25, 2016, my friend Nilaav* had called, his voice trembling. “I heard Xulhas Bhai has been murdered in his house.” A chill ran down my spine. I turned on the television.It was all over the news. Two gay rights activists had been hacked to death in Dhaka’s Kolabagan by a militant group. One was Xulhas Mannan, the other was Mahbub Rabbi Tonoy, murdered for being gay and publishing the first gay magazine, “Roopbaan” in Bangladesh.

Tears rolled down my face as I watched the visuals of Xulhas Bhai’s (Bhai is a Bangla term, means brother) lifeless body, lying in a pool of blood. An elderly woman was trying to lift him, pleading for help. “Get up! Why are you not helping me? Why is my son lying like this in front of the door?”.

Unable to watch this further, I switched off the television and locked myself in my room. I was afraid! I felt empty! I tried reaching out to my friends, but every number I called was unreachable. I found myself alone in an eerie void. I was unable to share my anxiety with anyone.

A little later, my phone rang and I could hear my friend Megh* sobbing. “None of us will survive. They will kill us all. My uncle knows I am gay. They will kill me too.” I was at a loss for words. What could I even have said at that moment to console him? Tears continued to stream down my face. I kept my voice low to hide my tears from my family. Megh hung up after a few minutes. We were just 20-year-olds, with no support and no one to tell us, “Don’t worry, everything will be okay. I’m here for you.”

Two days later, I learnt that Megh* had taken his own life that same night as. The official response from the then-home minister was shocking. “Our society does not allow any movement that promotes unnatural sex. Writing in favor of it is tantamount to criminal offense as per our law. We are also trying to find the militants.” It seemed as though the murder had been justified because of the victim’s sexual orientation. That day, I realised that murder may be a crime in my country, but not when the victims are queer people. The government didn’t condemn the murders. On the contrary, that year, it opposed the provision of gay rights in Bangladesh, branding them as anti-religious and anti-social.

Over time, my fear and loneliness started to wear off, and I started to gather my strength. I began writing blogs anonymously under a pseudonym. I realised there was so much to learn about building a movement. Though I was an electrical engineer, I studied law, joined a community-based NGO, and got involved in grassroots-level activism.

I didn’t want to protest against the state. I wanted to break the silence around queer issues. I wanted to unite and empower my community. I joined a Facebook group called Warrior*. By 2020, I was leading this group. Other like-minded individuals joined me.Today, numerous queer organisations have sprung up across Bangladesh, inspired by Warrior, as we continue decentralising and expanding this community-based activism.

The fruit of this movement is in small victories, like the one we achieved after rescuing Ritu’s partner Trisha from the conversion therapy her family had forced on her. Amid drizzling rain, the three of us went to seek legal advice from a lawyer. We wanted to ensure that Ritu would not be accused of abduction by Trisha’s family. To prevent this, Ritu planned to request court custody. The lawyer helped us prepare the documents for the court. But when we left, the fear remained that Trisha’s family might reveal her gender identity in court.

We got on a rickshaw, still thinking about these fears. And suddenly the drizzle turned into a relentless downpour. As I watched the rickshaw-puller continue to pedal us on our way, I realised that he did not have the luxury of stopping his work because of the rain. He knew that if he stopped, people who depend on him would go hungry. Just like him, I know that if we stop our work, the light of hope will be extinguished for the queer people of Bangladesh. At that moment, Ritu turned to me and said a simple “Thank you.” I understood that these words, though small, carried a profound depth of meaning. People like Ritu inspire me even more. I dream that after this storm passes, a rainbow will shine over this land.

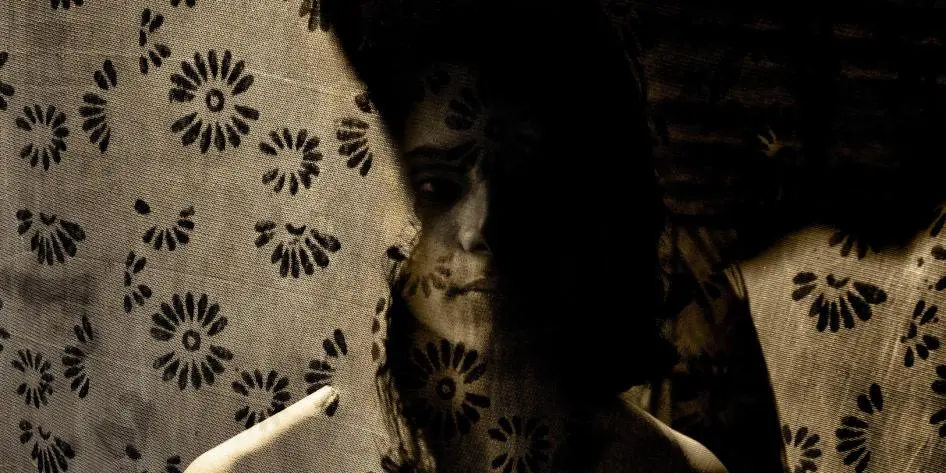

Photo Credits: 2013 Shahria Sharmin

By Jubdatul Jabed, Program Manager, Bangladesh