Senior Legal Officer at iProbono in Bangladesh, Arpeeta Shams Mizan, discusses the relevance of street law in promoting social justice in South Asia with Meenakshi Menon, Senior Program Manager for iProbono’s work across South Asia. Their conversation highlights the potential and challenges of delivering street law programs amidst the pandemic.

What makes street law relevant today? How does it help promote pro bono culture in South Asia?

Historically, street law programmes have provided information otherwise inaccessible to those marginalised by society. For instance, in the 1970s, during the civil rights movement, law students in the United States used street law to create rights awareness among the African-American community who were economically and socially excluded.

You may question the need for legal awareness initiatives in today’s information and tech boom, but findings from iProbono’s street law programmes suggest that while information might be easily available, people cannot exercise their rights until they can contextualise the information they have. Street law is an effective empowerment tool and can help you navigate and understand legal information you may already have.

Recently, we concluded a virtual street law programme on medical negligence and the law of torts in Bangladesh. Most of our participants were law students who study torts as part of their university curriculum. They knew the theory and principles of the law but did not know how it plays out in the legal system. Through stories, roleplay, and debates, we taught them how the law can be applied in real-life situations. Street law can be viewed as the bridge between lawyers who know the law and laypersons who know the context and require redress. When there is an exchange of ideas between them, both are enriched.

The Training of Trainers [ToT] session organised by iProbono on 16 November 2020 for street lawyers. Dr. Ridwanul Hoque, Professor of Law at the University of Dhaka, conducted this session on the applicability of the law of torts in Bangladesh, with a specific focus on negligence.

What inspired you to become a street lawyer? How has this shaped your professional journey?

During my first year of law school in Dhaka University, I regularly assisted on street law programmes organised by the seniors. When they explained the law through street law methods, I realised that I understood it even better than I did in class. This prompted me to become the coordinator of ELCOP’s (Empowerment through Law of the Common People) street law programme. During my Master’s programme at Harvard University, I designed a street law research project under the supervision of Professor David McQuoid Mason and had access to unlimited street law resources. At iProbono, I have the opportunity to take these experiences to different communities in Bangladesh.

Arpeeta met with children engaged in hazardous employment from multiple automobile workshops during a Street Law Programme on Child Rights in August 2019.

I now go beyond analysing the legal provisions and precedents — and understand how the law shapes society. We cannot educate people on issues like dowry or child marriage by simply telling them that it is against the law, without understanding their social context or gaining their trust. Conventional methods tell communities that if you accept dowry you will get arrested under the law. But dowry is rooted in patriarchy, so instead of just stating the law you have to try to understand the rationale behind legislation, explain that it does not betray religion to stop engaging in such practices, and convince them after listening to their context.

Once, during a street law session on child rights in a slum in Dhaka, I sensed that while the audience agreed with us that child labour is harmful for children and should not be encouraged, what was prescribed by institutions did not match their social reality and we had to engage with that premise.

What I value most about street law is that it allows me to interact with people and understand the perspectives of those whom I would have not met otherwise.

What are the key elements of a successful street law programme?

A successful street law programme should impart three key things – increased knowledge, increased skills and an enhanced set of values. For instance, when we conclude a street law lesson on medical negligence, the target group should understand medical negligence and the law of torts (knowledge), be aware of the institution or agency which can provide recourse in case of violation and the process on how to seek redress (skills), and they should believe in the values of human rights and corresponding civic duties (values).

iProbono, in collaboration with Empowerment through Law of the Common People (ELCOP), Manusher Jonno Foundation, Community Participation & Development (CPD) and Ain o Salish Kendra organised a street law workshop for children in hazardous employment in the Kamrangichor area of Dhaka, Bangladesh in November 2019. Arpeeta trained 12 undergraduate students of Law and Criminology from six universities in Bangladesh as part of this project.

Are there any thematic areas that you believe are better served through legal education rather than judicial avenues?

In 2019, ELCOP delivered a street law exercise bringing together Dalits and transgender people, who are some of the most marginalised communities in Bangladesh. The two groups seemed apprehensive about sharing space and were prejudiced against each other despite facing discrimination and abuse in their own ways. At the end of the exercise, however, they were able to overcome misgivings about the other community. They noted that they failed to realise that others are facing a different kind of discrimination and that to nurture pre-conceptions about any group or person defeats their fight for fair treatment of their own community.

Biases are deeply ingrained in our society, litigation will not solve this. Filing a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) may not have the desired impact on the psyche of society, and issues of discrimination and bias are better served by legal education programmes. Systematic prejudice and historic discrimination are not perceived as warranting litigation until there is proper rights education. Legal education cannot replace litigation but is a necessary support system.

COVID-19 has forced us to move our street law programmes online, what are the related challenges and advantages to this shift?

Street law has been adapted during the pandemic. Street law methodologies kept pace with the digital age to create rights awareness on social media platforms. The Hong Kong University, Street Law Inc. in Washington DC, and Street Law South Africa have designed and adapted lesson plans for online access. Other community legal education programmes can also be adapted in this way. For those with the resources and technical know-how, online platforms can be used to make the lessons visually sophisticated. However, there are disadvantages as not everyone has access to the internet or digital devices. A virtual platform also limits human interaction that makes it harder to convince the sceptics.

If you deliver lessons through recorded messages you cannot be sure that they have understood the message, there is a risk of misinterpretation and misuse. In addition, on conferencing platforms, people are not always comfortable and are fatigued from information overload, which may lead to desensitisation. So, while it makes sense to reap the benefits of online platforms, as justice advocates, we must strive to establish a human connection wherever possible, safely, and with due diligence.

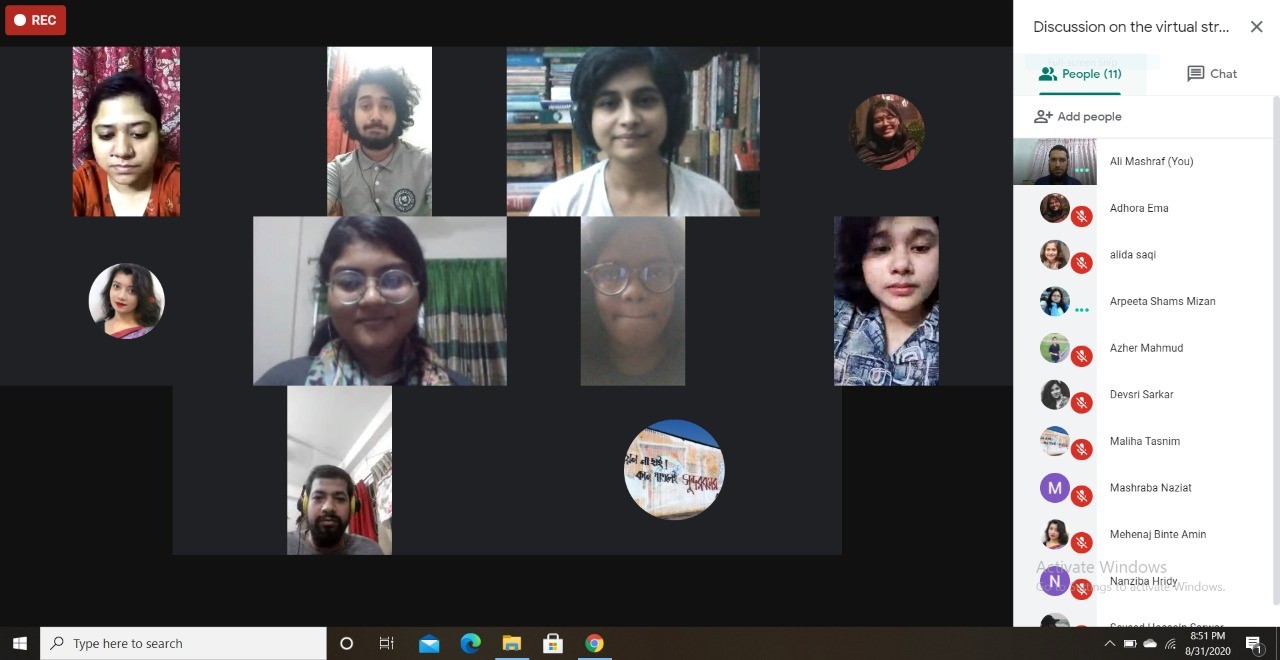

iProbono Bangladesh hosted an online discussion with street lawyers and trainers of the ‘Street Law on Child Rights Programme’ in September 2020.

How can we keep street law alive and thriving?

Institutionalisation of street law is crucial to keep it alive. Clinical legal education should become a mainstream academic activity, law schools in South Asia should include street law programmes in their curriculum and make it aspirational for students. Law teachers should also take more interest in exploring street law methodologies. Since the 1980s, there is a perception among donors that legal education or awareness programmes are obsolete. Countries that developed institutional frameworks for street law like South Africa and the USA could do so because they have funding. In South Asia, many students are poor and rely on part-time jobs to complete their education. It is not possible for them to volunteer their time and resources without getting reimbursed. In the long run, adequate funding can ensure that the cycle of injustice is broken, we need more donor organisations in the justice sector to support street law programmes and usher meaningful change.

What would you say to encourage your academic peers to engage their students in street law programmes?

Street law obliterates the barrier between you and the students, which allows you to learn from those who have a fresh perspective. If as a teacher of law you want to keep exploring and stay on pace, engaging with your students through street law is a great way to achieve that. It also alters your perspectives as a privileged law professional and helps you engage with society more widely. I think this consciousness of your privilege matters greatly while working in the field of law.

Where is iProbono’s street law programme headed in Bangladesh?

We will continue to engage in issues of discrimination that lack visibility in the development sector. For instance, on the potential of affirmative action and enforcement mechanisms against sexual and gender-based violence against women. Strengthening civil society organisations and social enterprises are key to iProbono’s wider mission; we hope to organise a street law campaign to support them with legal and compliance requirements in Bangladesh. We will also improve our street law resources through interesting digital advocacy ideas to engage the social media-savvy youth of today. Alternative forms of street lawyering including using theatre, art and other channels for storytelling are also on the cards.